If you’ve ever played a second of organized basketball, you’ve likely heard your coach discuss two types of scoring opportunities: Ones that come in transition and ones that come in the half-court.

When we’re in transition (when our team has a fast break), our goal is to score quickly. We want to push the ball up the court, make easy passes to open teammates, and get open layups before the defense has time to get themselves set.

In the half-court, all five of the other team’s defenders are already set by their basket. Because we don’t start with an advantage, we have to find ways to create an advantage – that’s the purpose of any of the hundreds of offenses a team can run.

But ask yourself – Does this tell the full story? Will I only ever find myself in situations where our team either has a full-on, race-to-the-rim fast-break opportunity or a slow-moving, defense-perfectly-set half-court possession?

No! Of course not! Sometimes, most or all of the other team's defenders will be between me and the basket, but they won’t be perfectly set – they’ll still be running up the court along with me and my teammates.

This is called the secondary break. Any time my team is running up the court at the same time as the defense is trying to get back and defend, but we don’t have an obvious numbers advantage, we’re in the secondary break situation.

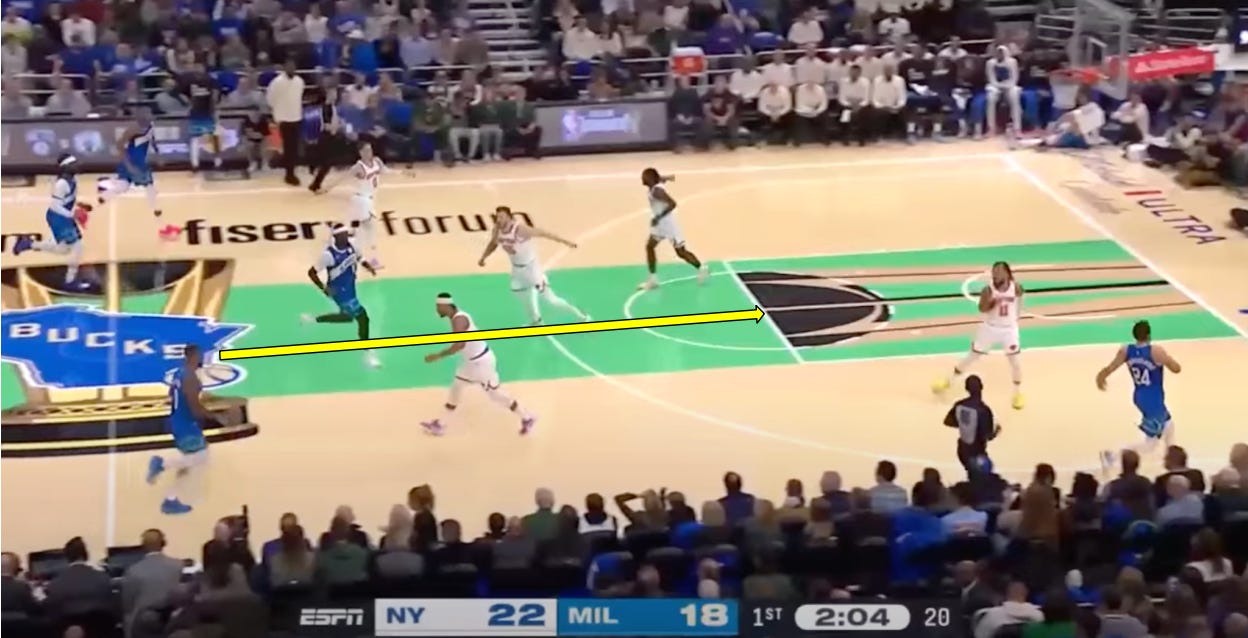

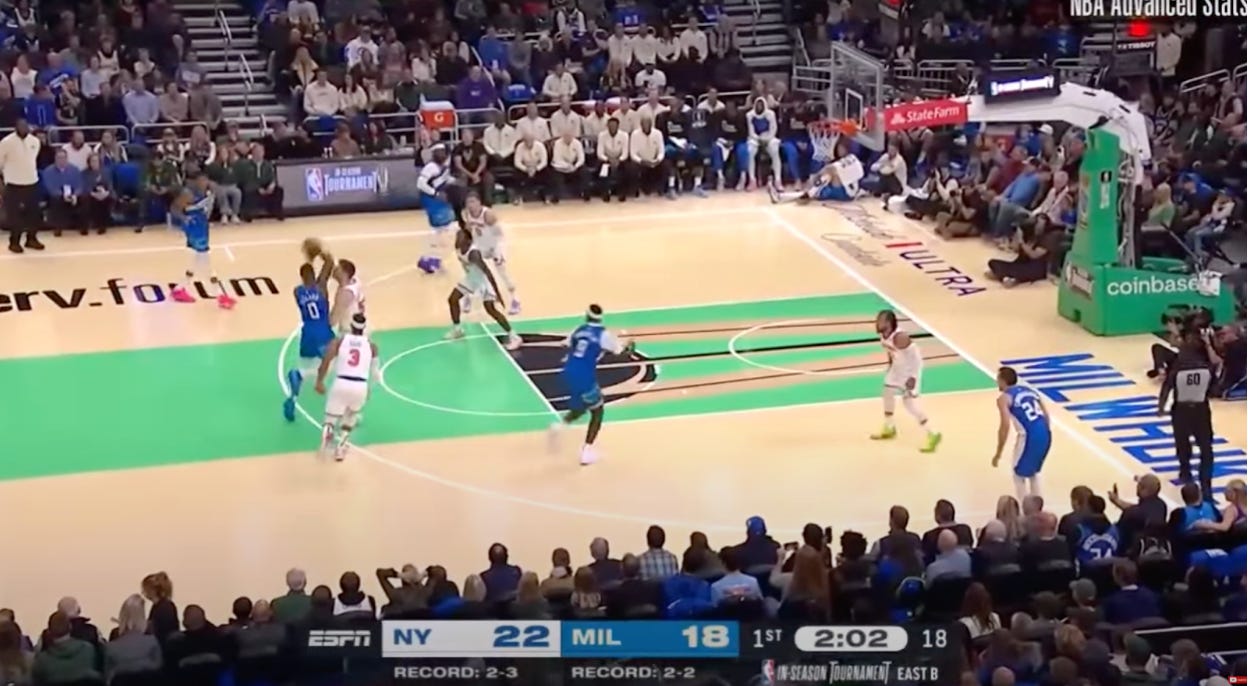

Check out this clip of Damian Lillard running a secondary break

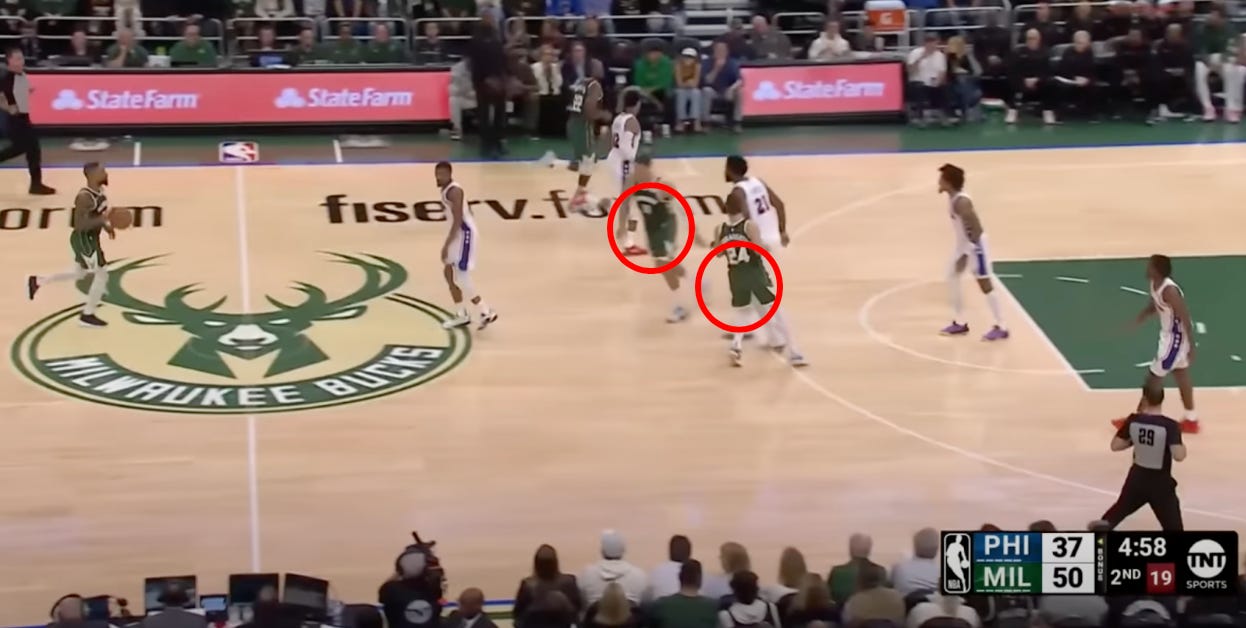

Notice where the play starts.

The Bucks don’t have a numbers advantage here, but the defense isn’t set either. Lillard’s head is toward the rim because he sees the open space there.

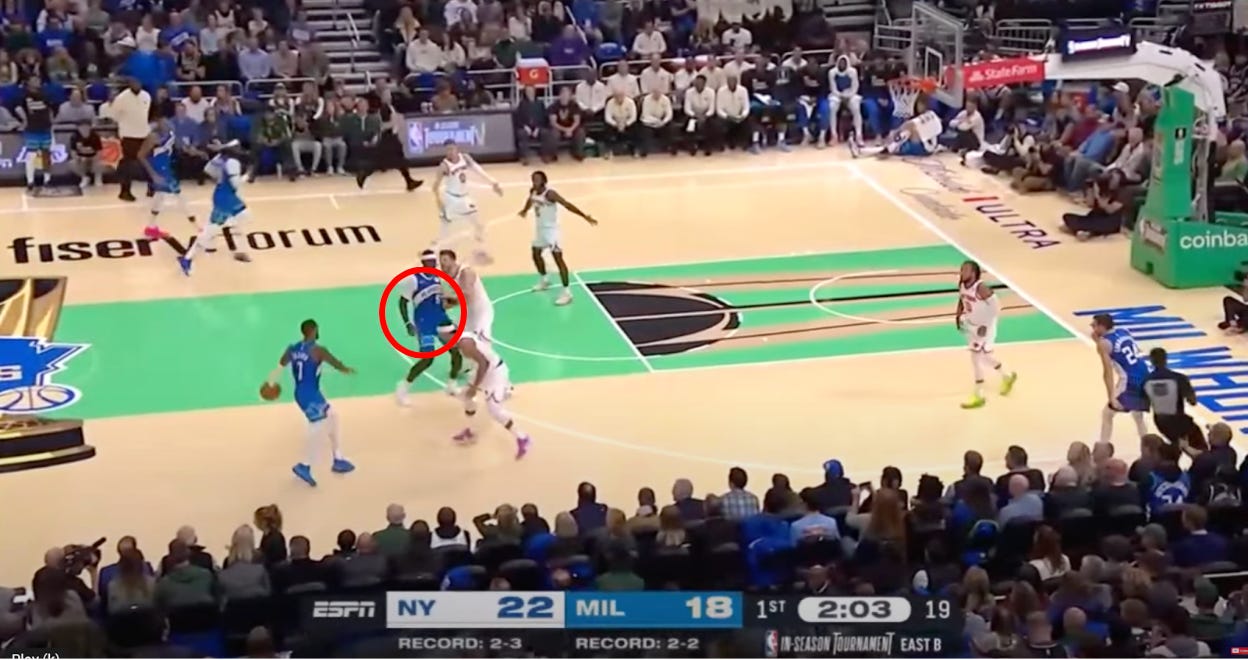

Portis comes to set a screen. This is interesting – By accepting the screen, Lillard is actually moving away from the open space and toward the defense. Normally, we’d want Lillard driving to his right hand because that’s where his scoring opportunity is. Jalen Brunson is the only defender on the right side of the court, so if Lillard beats his man right, he’ll either get a wide-open layup, or Brunson will help down and leave Pat Connaughton in the corner for a wide-open three – and that would’ve been a perfectly acceptable option.

Lillard is a high-level playmaker, though. He doesn’t always need to make the most obvious play to be effective. Portis is already there setting the screen, so Dame chooses to accept it, and the Knicks get caught in a scramble trying to defend the ball. Lillard ends up being guarded by his man and by Portis’s man.

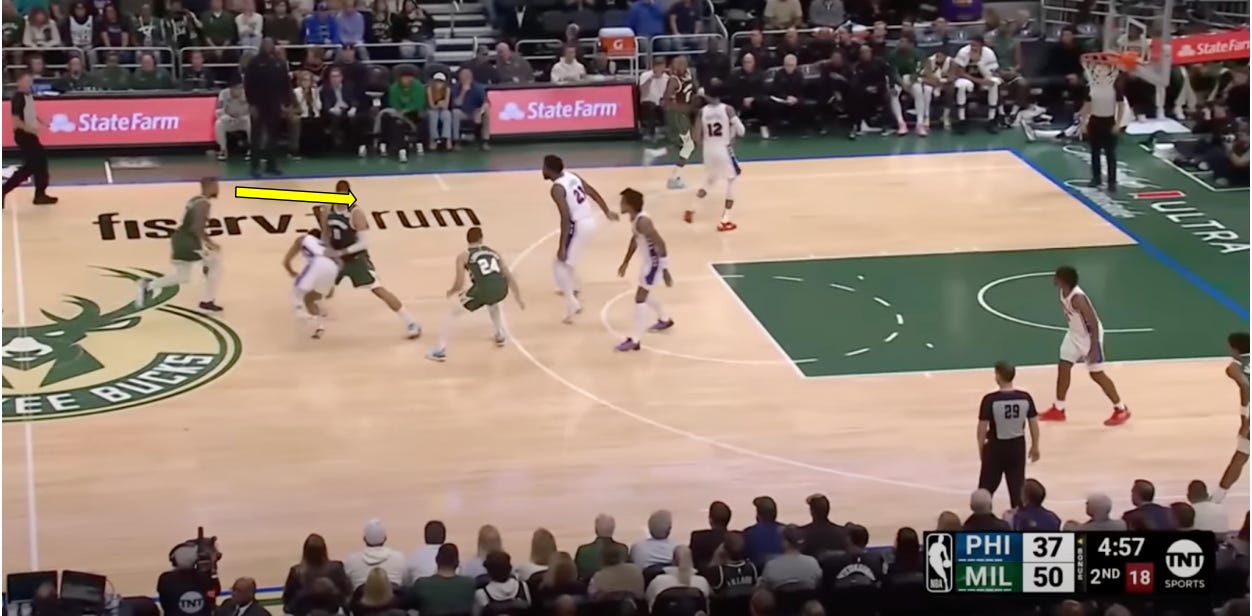

And here’s where it gets interesting. Look at the direction of Lillard’s eyes. He isn’t looking at Portis rolling to the rim; he’s looking at the lone defender in a position to stop his roller.

If that help defender were to drop down and try to prevent Portis from scoring at the rim, Lillard would have a wide-open shooter on the wing.

The defender doesn’t drop down, though. He gets caught in no-man’s land trying to defend both the shooter and the roller. Dame sees this and hits Portis for a wide-open layup.

Let’s look at one more example of Lillard.

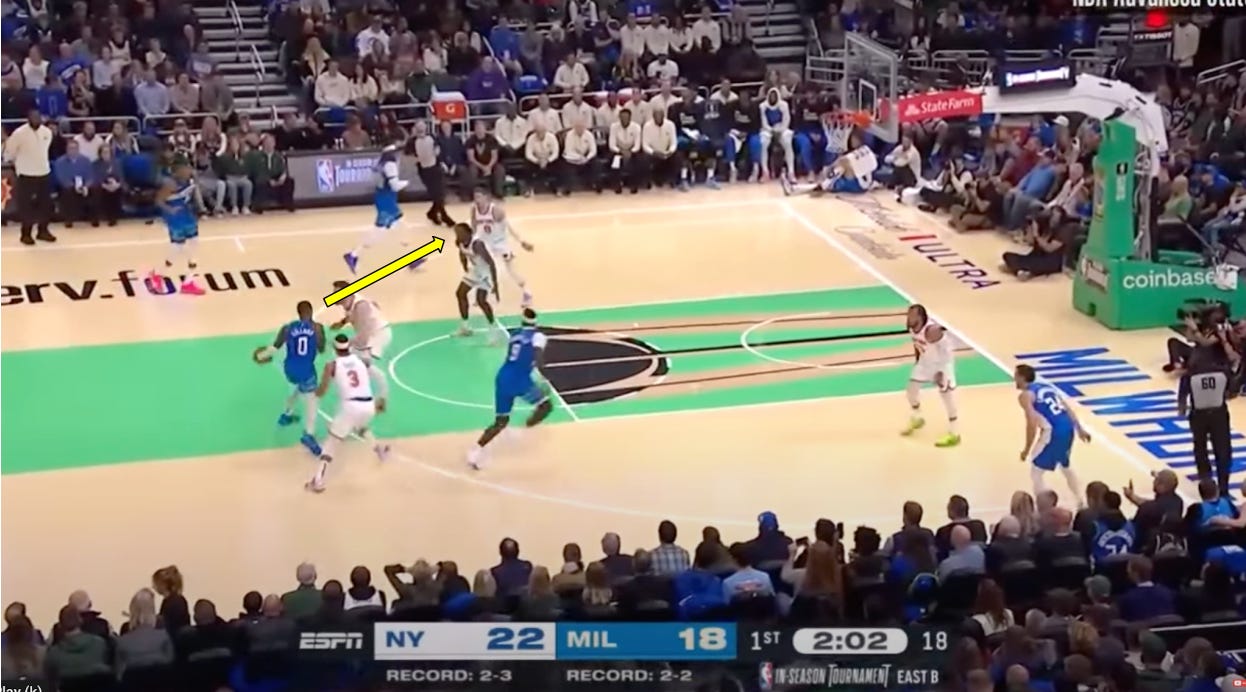

Once again, the Bucks are without a numbers advantage here. They’re facing defenders who are still scrambling to get set. It’s a secondary break.

When the play starts, there’s no obvious point of attack for Dame. Unlike the last example, where there was a wide open space right near the rim, this set is a bit more disorganized.

What does Lillard have to work with then? Well, two things: The fact that the defense is still in a scramble and the fact that he has a screener coming his way – in this case, he has two potential screeners, actually.

Dame decides to take Brooke Lopez’s screen. Why? Well, probably because he knows it’ll result in a better mismatch if the defense switches the screen. He’d rather have a one-on-one with Embiid than with Kelly Oubre.

Once again, take a look at Lillard’s eyes. Unlike before, when he was reading the help defenders, now he’s reading the screener’s defender – his eyes are on Embiid.

Lillard can put the ball in the basket from long range, so Embiid’s decision to hang back and guard against a drive is exactly what Dame wants to see. He goes right for the open space and pulls the trigger – that’s three easy points for his team.

So, what can we learn from these two examples?

Unless you’re one of the most elite high school players in America, your coach probably doesn’t want you pulling up from 30 feet on the secondary break. And unless you really know how to read the game at a high level, we probably don’t want you opting to reject an open drive to the rim in favor of a ball screen that leads you toward the help defense. But there is still a lot we can take away from all this.

First and foremost, always be in attack mode during the secondary break!

Just because you don’t get an uncontested run out doesn’t mean your team doesn’t have an advantage. Any time the defense is scrambling, you have an opportunity to score, or to create for teammates. There’ll be more obvious openings toward the rim, the help defense won’t be in great position, and even simple actions (drives to the paint, attacking ball screens, advancing the ball to a cutter) will create defensive lapses – somebody will wind up wide open.

If you don’t attack quickly, though, all these advantages will disappear. The defense will have time to get set, and you’ll have lost your opportunity for an easy bucket.

Secondly, learn to see open space.

Beating your defender is easy in the secondary break. You’re moving fast to advance the ball up the floor, and he’s backpedaling into position. All it takes to go by him is one quick move. But, if you aren’t good at recognizing open space, the move you make to beat your defender won’t be worth anything. You’ll run right into the help defense, or you’ll pass up an open jump shot in favor of a contested finish near the rim.

In the two examples we looked at today, Lillard had screeners to help him create offense. But remember, he’s playing against NBA defenders. These guys know how to defend in transition, and they’re less likely to make a mistake in help defense.

Even good high-school teams aren’t capable of getting themselves that organized during a secondary break, though. You won’t need a screener to help you create open space. The space will already be there for you to attack – so attack it. Maybe it’s open space for a jumper; maybe it’s open space for a layup – maybe it’s open space that you aren’t able to attack but that a smart teammate can cut to earn themselves two easy points.

If you don’t see the space, you can’t exploit it.

Lastly, always be thinking one move ahead.

In the first example, Lillard focused almost all his attention on a single help defender. He wasn’t concerned about his man or about coming off the screen – he was concerned with the one guy on the other team who had a decision to make: “Will I guard the shooter, or will I guard the roll man?”

You can think ahead, too. If I beat my defender, I’m not just blindly barrelling toward the rim until I run into somebody. I have my head up so I can survey the help defense. Who can stop me, and if he tries, who will he have to leave open?

Reading help defense is easy in the secondary break. There’s tons of open space, and defenders are distracted. If you can get used to staying one step ahead of the D in these situations, your ability to read the help will also translate to the half-court.

Next time you have a game (or are playing pickup/scrimmaging in practice) keep these tips in mind. Any time our team gets a defensive rebound, we’re in a position to attack the secondary break – and a well-executed secondary break should always result in a high-quality shot.